This content has moved to http://oalabs.openanalysis.net/2015/06/04/malware-persistence-hkey_current_user-shell-extension-handlers/

Update June 8, 2015: Harlan (@keydet89), of Regripper fame, has updated Regripper to identify this persistence mechanism. Details can be found on his blog. On a related note, Harlan takes requests for Regripper features! He was pretty awesome about turning this one around quickly so if you need a new feature just e-mail him.

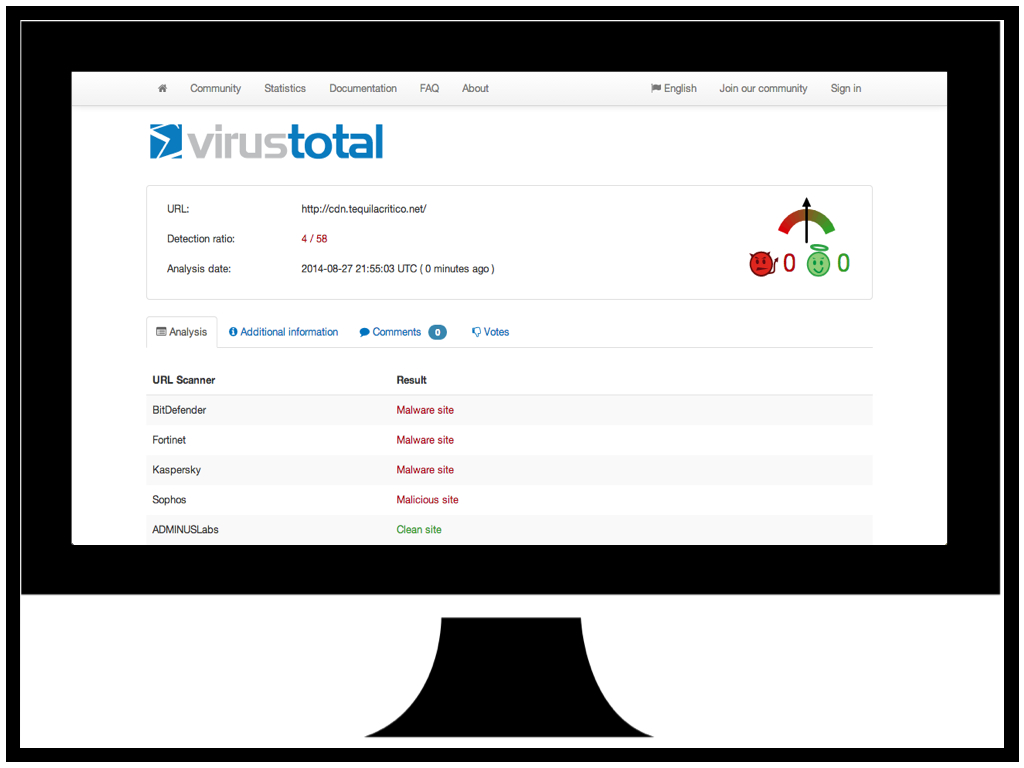

I was recently exposed to a new (to me anyway) method of persistence that the Bedep malware is using. The novel aspect of this persistence method is that it doesn’t require administrator rights and it evades my two favourite persistence detection tools: Autoruns, and RegRipper. The persistence method requires the creation of a per-user shell extension handler where the shell handler DLL is the malware that requires persistence.

Known Methods of Persistence Through Shell Extension Handlers

Using a shell extension handler is actually a fairly well known, and well documented trick that malware uses for persistence. However, there seems to be a gap in the tooling provided to detect this persistence (autoruns, regripper); these tools focus on detecting Shell Extensions that have been registered for all users on the host. If a Shell Extension is only registered for a single user (Current User) it can evade detection.What Is a Shell Extension Handler?

Explorer.exe is what is referred to as the default “shell” for Windows; it is the GUI that is used to interact with the OS. Explorer provides the ability to extend its functionality using COM objects called Shell Extensions. To quote this excellent article on building shell extensions "a shell extension is a COM object that adds features to Explorer”.A common example of a Shell Extension would be the “WinZip” options that appear when you right click on a file after installing the WinZip program.

|

| WinZip Shell Extensions in action |

Registering a Shell Extension Handler

Shell Extensions need to be registered with the Shell before they can be used. How they are registered is the key to this stealthy persistence mechanism. There is a good overview of how to register a Shell Extension on MSDN. Some excerpts from that article have been copied below to quickly illustrate how a Shell Extension might be registered.Step 1 - CLSID and Path To DLL

First the Shell Extension handler has to be assigned a unique GUID called CLSID. Then the CLSID is added to the registry HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\CLSID and the InprocServer32 key is added signifying that this is an in-process server. The default value for the InprocServer32 key is set as the path to the Shell Handler DLL. |

| Add Shell Extension CLSID to registry with DLL location. |

Step 2 - Assigning the CLSID to File Type or Shell Object

Once the Shell Extension has been associated with its CLSID the CLSID needs to be associated with a File Type or a Shell Object that it is going to provide extra functionality for. This is done by adding the CLSID as a key to the registry HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\<ProgID>. In this example the CLSID will be added as a ContextMenuHandler to all File Types associated with MyProgram. |

| Associate CLSID with MyProgram. |

Step 3 - Approving CLSID for Use

If the EnforceShellExtensionSecurity key has been set then the CLSID will need to registered as Approved before it can be used. Since the EnforceShellExtensionSecurity value may be set per-user instead of globally it is best practice to add the CLSID to HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Shell Extensions\Approved key by default. |

| Add CLSID to approved Shell Extensions. |

The Trick is HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT

The HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT key is a virtual representation of both the HKEY_CURRENT_USER and HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE. Where settings that are global to the host (apply to all users) are stored in HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE and settings that are specific to a single user are stored in HKEY_CURRENT_USER. More information can be found here.The trick is that when a key is stored in HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT by default it is stored in HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE. However, when a key is read from HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT it is read from HKEY_CURRENT_USER first and if no key exists then it is read from HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE. This means that when a Shell Extension is registered HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT it is stored in HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE which requires administrative privileges, and if the EnforceShellExtensionSecurity key is set then the Shell Extension must also be registered in the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Shell Extensions\Approved key. However, when Explorer.exe loads the Shell Extensions for a user it checks the Shell Extensions in HKEY_CURRENT_USER first before checking in HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE.

If malware wants to install a Shell Extension without administrator privileges that will run for the current user it can individually add entries for the Shell Extension in HKEY_CURRENT_USER instead of HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT. An added advantage of this is that since the Shell Extension is only registered for the current user it doesn’t need to be registered in HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Shell Extensions\Approved regardless of the setting in EnforceShellExtensionSecurity.

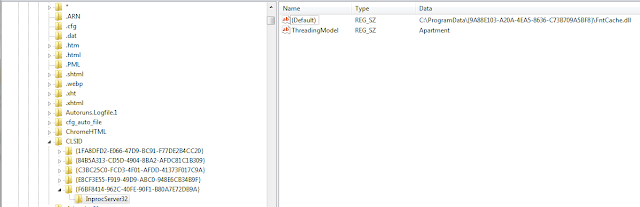

Here we see Bedep has taken advantage of this trick to install a Folder Extension Shell Extension handler in HKEY_CURRENT_USER. The FntCache.dll is the persistence DLL used to initialize Bedep.

|

| Bedep Shell Extension CLSID installed in Current User. |

|

| Bedep CLSID associated as Folder Extension. |

A Blind Spot in Our Incident Response Tools

The problem with the two tools I mentioned; RegRipper (shellext.pl plugin) and Autoruns is that they rely on the Shell Extension to be registered using the standard method with HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT. Because of this they don’t individually enumerate the Shell Extensions in HKEY_CURRENT_USER. Here we see there is no trace of the Bedep persistence Shell Extension handler in the results of Autoruns on the host infected with Bedep. |

| Autoruns is unable to find Bedep Shell Extension. |

Building a Timeline Using Cached Shell Extensions

When a Shell Extension is loaded for the first time (per user) a key is stored in HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Shell Extensions\Cached. More information on this registry key can be found here. We can see below that the Bedep Shell Extension CLSID has an entry in the Cached key. |

| Bedep Shell Extension CLSID has an entry in the Cached key. |

Bedep Shell Extension CLSID = {F6BF8414-962C-40FE-90F1-B80A7E72DB9A}

IDriveFolderExt CLSID = {3EC36F3E-5BA3-4C3D-BF39-10F76C3F7CC6}

Unknown Mask = 0xFFFF

The binary value that is assigned to the Cache key contains a cache control flag, some unknown data, and the time the Shell Extension was first loaded stored in 64bit little endian FILETIME.

|

| Shell Extension Cached entry showing first loaded time. |

Automated Shell Extension Timeline Generation and Shell Extension Detection

I have built a tool (LocalShellExtParse.py) to help automate the task of generating a “first loaded” timeline for Shell Extensions and identifying Shell Extensions that are only installed for the current user. I know this probably would have been better as a RegRipper plugin but Python is the future, and we need to collect some extra information that RegRipper doesn’t currently parse.Data Collection

This is an “offline” tool that parses entries in the NTUSER.DAT and UsrClass.dat files. To use the tool you will first need to collect the files from the host that you want to analyze. I prefer FTK Imager but any tool that allows you to carve system files will work.Everyone knows that NTUSER.DAT is located in %userprofile% but UsrClass.dat may be less well understood. When viewing a live registry under HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\ there is a key called “CLSID” that shows all the CLSIDs for the current user. The data for this key is not stored in NTUSER.DAT it’s actually stored in the UsrClass.dat file located in; %userprofile%\AppData\Local\\Microsoft\Windows\UsrClass.dat.

Data Parsing

Once the files have been collected the can be parsed by LocalShellExtParse.py to produce;- a timeline of the first time each Shell Extension has been loaded by the user

- a list of all Shell Extensions that have been loaded by the user and are only installed for that user.

|

| LocalShellExtParse.py shows Bedep Shell Extension and Bedep DLL "ieapfltr.dll". |

The tool can be found on GitHub here. Note* this tool has only been put through a small amount of testing, use at your own risk. This tool should only be used to prove the existence of a persistence mechanism via a per-user Shell Extension. Do not rely on this tool as proof that no persistence mechanism exists.